25 August 2023

By highlighting the story of Manuel García fils (1805-1906), the Centre Européen de Musique is paying tribute to a polymath, teacher, singer, scientist and researcher, a member of a unique family saga: the García dynasty. The invention of the laryngoscope by Manuel García Jr. in 1854 was no accident, and the acquisition by the Centre Européen de Musique of this priceless relic is a powerful symbol that fully embodies the missions that the CEM has set itself in the 21st century: building bridges between the present and the past; uniting the arts, sciences and humanities. After a second episode devoted to the pedagogue Manuel García fils, discover the third in our historical series, written by Thomas Cousin, Doctoral Candidate in History and Musicology at the Université Libre de Bruxelles/Sorbonne Université.

When he moved to England, Manuel García was a renowned teacher whose scientific method attracted many students. However, his teaching was limited to theoretical knowledge, as he was unable to observe the larynx in action. This was done in 1854, when he became the first to use a dentist's mirror to "describe the observations made inside the larynx during the act of singing", observing for himself the appearance of the glottis in both chest and falsetto registers. Manuel García had just invented a revolutionary instrument for singing and medicine. The pedagogue was paving the way for a new field of scientific research: laryngology.

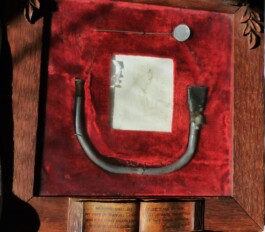

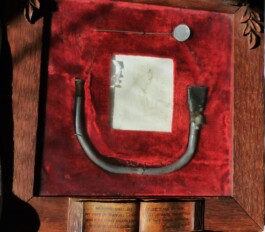

The laryngoscope invented by Manuel García fils is one of the key pieces in the García Memorabilia acquired by the CEM.

At the end of the 1850s, the neurologist Ludwig Türck and the physiologist Johann N. Czermak were among the first scientists to understand the revolutionary scope of Manuel García's novel instrument, and were to use the laryngoscope as a medical tool for the first time. Although Dr Czermak wrote in 1858 that Manuel García "seems to have been the first to have succeeded in making the inner parts of the vocal organ of living man accessible to observation", it is interesting to note that the scientific community of the time tried to attribute the paternity of this invention to one of his peers, minimising or even obliterating García's name. Paradoxically, these upheavals led to the subsequent recognition of Manuel García who, in the following letter to Dr Larray dated 4 May 1860, describes the circumstances surrounding his discovery:

The idea of using mirrors to study the inside of the larynx during the act of singing had occurred to me for a long time and at various times; but I had always rejected it, believing it to be impracticable. It wasn't until 1854 that, finding myself on holiday in Paris during the month of September, I resolved to clear up my doubts and see what was feasible about my idea. I was going to ask Charrière if he didn't have a small mirror which, attached to a long handle, could be used to examine the gullet. He replied that he had a small dentist's mirror, which he had sent to the London exhibition in 1851 and which nobody had wanted. I bought it (I think for 6 francs) and, equipped with a second hand mirror, I returned to my sister's house very impatient to begin my tests. I placed the small hand mirror against the uvula and saw the gaping larynx as it is described in the first three pages of the memoir you know. Soon after my return to London, the fog came to put a desperate obstacle in the way of my studies. I turned to Mr Williamson, Professor of Chemistry at the University of London, to ask him for a bright and abundant artificial light, as my oil lamp gave very inadequate light. He showed me the light provided by burning lime in the known mixture of oxygen and hydrogen. Unfortunately my apparatus was very imperfect and my attempts failed. Electric light was no better. I was therefore reduced to using my devices only when the sun appeared quite rarely. As the main aim of my research was to determine the role played by each intrinsic muscle of the larynx in the voice mechanism, I had to go back to dissecting. It was to Mr Williamson that I again turned for help in obtaining larynxes. He introduced me to Dr Sharpey, Professor of Physiology at the same university and Secretary of the Royal Society. As soon as Dr Sharpey heard what I was up to, he instructed the boy in the lecture theatre to supply me with as many larynxes as I asked for. He further advised me to write a paper on what I had observed, offering to read it to the R.S. as soon as it was completed.

On 22 March 1855, Manuel García submitted his Memoir Physiological Observations on the Human Voice to the Royal Society of London. On 24 May, the Memoir was presented by Dr Sharpey and recorded in the Proceedings of the Royal Society. The Memoir began with these words:

The purpose of the following pages is to describe the observations made inside the larynx during the act of singing. The method I have used has, if I am not mistaken, not been tried by anyone. It consists of placing a small mirror, attached to a long handle suitably curved, at the top of the pharynx of a subject. The subject must face the sun, so that the light rays falling on the small mirror can be reflected on the larynx. To the observations provided by the image reflected by the mirror, we will add our own deductions.

In 1862, the University of Königsberg awarded Manuel García the honorary title of Doctor of Medicine. Dr García was invited to the seventh session of the International Medical Congress in London in 1881 to present his work on the larynx and vocal apparatus. Finally fully recognised by the scientific community, the maestro di bel canto became known as the "Father" of the laryngoscope.

25 August 2023

By highlighting the story of Manuel García fils (1805-1906), the Centre Européen de Musique is paying tribute to a polymath, teacher, singer, scientist and researcher, a member of a unique family saga: the García dynasty. The invention of the laryngoscope by Manuel García Jr. in 1854 was no accident, and the acquisition by the Centre Européen de Musique of this priceless relic is a powerful symbol that fully embodies the missions that the CEM has set itself in the 21st century: building bridges between the present and the past; uniting the arts, sciences and humanities. After a second episode devoted to the pedagogue Manuel García fils, discover the third in our historical series, written by Thomas Cousin, Doctoral Candidate in History and Musicology at the Université Libre de Bruxelles/Sorbonne Université.

When he moved to England, Manuel García was a renowned teacher whose scientific method attracted many students. However, his teaching was limited to theoretical knowledge, as he was unable to observe the larynx in action. This was done in 1854, when he became the first to use a dentist's mirror to "describe the observations made inside the larynx during the act of singing", observing for himself the appearance of the glottis in both chest and falsetto registers. Manuel García had just invented a revolutionary instrument for singing and medicine. The pedagogue was paving the way for a new field of scientific research: laryngology.

The laryngoscope invented by Manuel García fils is one of the key pieces in the García Memorabilia acquired by the CEM.

At the end of the 1850s, the neurologist Ludwig Türck and the physiologist Johann N. Czermak were among the first scientists to understand the revolutionary scope of Manuel García's novel instrument, and were to use the laryngoscope as a medical tool for the first time. Although Dr Czermak wrote in 1858 that Manuel García "seems to have been the first to have succeeded in making the inner parts of the vocal organ of living man accessible to observation", it is interesting to note that the scientific community of the time tried to attribute the paternity of this invention to one of his peers, minimising or even obliterating García's name. Paradoxically, these upheavals led to the subsequent recognition of Manuel García who, in the following letter to Dr Larray dated 4 May 1860, describes the circumstances surrounding his discovery:

The idea of using mirrors to study the inside of the larynx during the act of singing had occurred to me for a long time and at various times; but I had always rejected it, believing it to be impracticable. It wasn't until 1854 that, finding myself on holiday in Paris during the month of September, I resolved to clear up my doubts and see what was feasible about my idea. I was going to ask Charrière if he didn't have a small mirror which, attached to a long handle, could be used to examine the gullet. He replied that he had a small dentist's mirror, which he had sent to the London exhibition in 1851 and which nobody had wanted. I bought it (I think for 6 francs) and, equipped with a second hand mirror, I returned to my sister's house very impatient to begin my tests. I placed the small hand mirror against the uvula and saw the gaping larynx as it is described in the first three pages of the memoir you know. Soon after my return to London, the fog came to put a desperate obstacle in the way of my studies. I turned to Mr Williamson, Professor of Chemistry at the University of London, to ask him for a bright and abundant artificial light, as my oil lamp gave very inadequate light. He showed me the light provided by burning lime in the known mixture of oxygen and hydrogen. Unfortunately my apparatus was very imperfect and my attempts failed. Electric light was no better. I was therefore reduced to using my devices only when the sun appeared quite rarely. As the main aim of my research was to determine the role played by each intrinsic muscle of the larynx in the voice mechanism, I had to go back to dissecting. It was to Mr Williamson that I again turned for help in obtaining larynxes. He introduced me to Dr Sharpey, Professor of Physiology at the same university and Secretary of the Royal Society. As soon as Dr Sharpey heard what I was up to, he instructed the boy in the lecture theatre to supply me with as many larynxes as I asked for. He further advised me to write a paper on what I had observed, offering to read it to the R.S. as soon as it was completed.

On 22 March 1855, Manuel García submitted his Memoir Physiological Observations on the Human Voice to the Royal Society of London. On 24 May, the Memoir was presented by Dr Sharpey and recorded in the Proceedings of the Royal Society. The Memoir began with these words:

The purpose of the following pages is to describe the observations made inside the larynx during the act of singing. The method I have used has, if I am not mistaken, not been tried by anyone. It consists of placing a small mirror, attached to a long handle suitably curved, at the top of the pharynx of a subject. The subject must face the sun, so that the light rays falling on the small mirror can be reflected on the larynx. To the observations provided by the image reflected by the mirror, we will add our own deductions.

In 1862, the University of Königsberg awarded Manuel García the honorary title of Doctor of Medicine. Dr García was invited to the seventh session of the International Medical Congress in London in 1881 to present his work on the larynx and vocal apparatus. Finally fully recognised by the scientific community, the maestro di bel canto became known as the "Father" of the laryngoscope.

Playlist